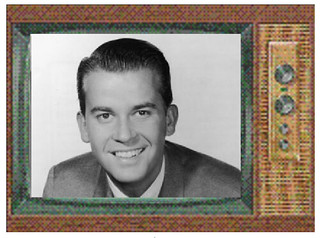

The passing of Dick Clark this week has sent me on one of those nostalgic trips through my childhood that makes me think how great some things seemed then, but also how much better and worse things are now.

The passing of Dick Clark this week has sent me on one of those nostalgic trips through my childhood that makes me think how great some things seemed then, but also how much better and worse things are now.

American Bandstand was a simple enough concept — play some new music and show kids dancing to it — but its cultural significance was a result of the way it brought people together, both inside the studio walls and outside. Millions of people gathered around their TV screens to see what this group of kids were digging and how they danced. “It's got a good beat and you can dance to it” became a punchline largely because, for most big rock and roll songs of the time — and still today, really — it was truth.

Dick Clark stood at the center of this with a clear understanding of music's ability to unite people. In an era where racial segregation was the norm, he brought Caucasian & African-American performers onto the show seamlessly, pushing boundaries without feeling the least bit unobtrusive. “The Twist” was just a dance, after all. Anyone could do it. Just as importantly, though, Clark had a keen ear for what music was worth playing. American Bandstand found good songs and made them hits. If all those viewers saw those kids really digging a record, they wanted it.

Who has that influence now? Who's out there looking for new music and showing the world what's good? Who are the modern tastemakers?

As Frank Zappa explained in this video, the music industry went into decline the moment that record labels began to assume the tastemaker role that Clark and others held during the 60s:

In the heyday of Bandstand, record labels never tried to be arbiters of taste. They threw everything against the wall, saw what stuck, and tried to make more of what did. They gambled a lot more, and sometimes they won. We don't see that in popular music anymore. By assuming the role of tastemakers that Dick Clark and other DJs held, the labels became the gatekeepers. They claimed the power to say what was good and what wasn't, turning the task of getting signed to a record deal into a race to the top of a mountain. Never mind that the one-sided nature of those contracts meant the mountain was made of feces. Signing a record deal meant you “made it”.

Of course, we all understand now that this is not the case. Signing a record deal means giving someone else the right to get paid for what you recorded.

After becoming the gatekeepers, the big labels consolidated to the point where now only three giant corporations control a whopping 75% of recorded music. They found loopholes in payola laws to prevent disc jockeys from becoming influential enough to tell listeners what's good. Only they could say that. Relaxing media restrictions to allow one or two corporations to buy up radio only consolidated their power further. Radio is incapable of breeding tastemakers now. Labels simply feed radio a pre-selected playlist and practically demand that we buy in, and what they tell us is good now is often determined by algorithm more than by inspiration.

That might explain why listening to the radio today sounds like listening to the decline of an empire. Everything is rigidly programmed, and nothing is left to chance. American Bandstand was successful because it took chances musically. It put new sounds on TV and gave its audience something different and exciting. As the big labels consolidated and turned more and more conservative, though, they stopped giving most new sounds a chance and only released music that some algorithms suggested would sell millions. You can hear the end result on the radio now — an endless barrage of stale club music, interrupted only by commercials and the occasional Adele tune.

In the late 90s, as radio consolidation was sweeping the nation, MP3.com started showing music fans how different things could be. Just like that, the Internet made distributing music so much easier. 15 years later, independent music is flourishing, thanks in no small part to the Internet, and many more artists are discovering ways to make a living on their own without a record deal.

The problem remains, though — how do you find the good music? Sure, lots of people are out there making good music, but most of them still struggle to get heard. Not every indie band is capable of thinking up an awesome gimmick that will get them tens of millions of views on YouTube:

Is there room then for new tastemakers, new Dick Clarks, new guiding hands that point people to something great? Some would suggest that indie music no longer needs a Dick Clark now, because crowdsourcing takes care of everything. You hear a song, you like it, you tell your friends, who tell their friends, and on down the line until the band becomes popular enough to support itself. Then those bands you like get fed into more algorithms, which turn out more music liked by those who like the bands you like.

Could you imagine rock & roll being discovered this way? Doesn't feeding people similar music based on their own taste all the time reduce the chance that they'll ever hear something truly original that they just might like? And what happens when the algorithm goes wrong? After all, if you like Edith Piaf, you probably don't want the computer to feed you Norah Jones. (Yes, that actually happened to a friend of mine.)

What's even worse is that most people simply don't differentiate between major label releases and indie releases. They just hear a song they like, they tell their friends about it, and everyone buys it, often oblivious to the fact that their money doesn't go to the artists, but to lobbyists in Washington who convince Congress to pass stricter copyright laws that make it increasingly harder to share any music. We stopped SOPA, sure, but they'll try again.

It's been my hope for a while that music podcasters would fill this void, finding and sharing the new indie sounds that would get people listening and/or dancing. Eight years in, though, podcasting is merely micro-media, just scraping the edges of a few genres. Has any podcast had a tangible impact on music? Does the niche nature of the medium (not to mention the licensing headaches that surround music in general) even allow for this to happen? Or do music podcasts simply miss that visual element that Clark — and later, MTV — exploited so well? After all, it's one thing to hear a song, but it's another thing entirely to watch a room full of teenagers dancing to it and try to emulate what they're doing in your living room.

Indie music might be thriving, and the Internet might eventually break the gatekeepers, even as we fight to make sure it's not the other way around, but modern music still feels like it needs the tastemakers, the influencers, the enablers, the guiding hands that can point those who want new music to the quality stuff. Dick Clark was once the king of the tastemakers. Alas, the king is dead now, and “long live the algorithms” seems to be the cry that proceeds him. Maybe I'm romanticizing a relic from a bygone era, but when it comes to new music discovery, I would take one American Bandstand over 10,000 Pandoras any day of the week. Indie music could make pretty good use of a relic like that right about now.

How do you fix what you didn’t realize was broken? I’ve become somewhat fond of Pandora and the music it says I like. I never really thought about what was happening to the music. I do remember how American Bandstand and MTV (in its early days) brought music I never heard but loved. Where else would you hear “I wanna be a Lifeguard” or “Surface Tension” or “Vienna” or even Devo’s version of “Satisfaction?” I remember going to the record stores (something ELSE you can’t do any more) and going through a certain artist’s collection to find something new. That’s how I found many of my favorite songs. Did I buy bad music? Sure. I also got some stuff that will always love and enjoy.

I hope that podcasts like Dave’s Lounge will continue to at least try to bring us a taste of something different. As it turns out, the only “new music” I’ve bought lately has been artists that I first heard on Dave’s Lounge. I still listen to and use Pandora-but with my eyes a bit more open to the formula that’s been used on me. FIGHT THE POWER!

OK, time to give the soap box to someone else to shout from…

The troubling thing Dave, when I was a sprog I had scant funds for anything, DJs like John Peel directed me, via radio, to who I should like and I chose. I would take the aforementioned scant funds to my record man, who happened to be Richard Branson’s associate, down in Liverpool at the new Virgin Records store, and I would buy my gatefold LP, with lyrics, posters, stickers and I would cherish that for a month or more, wearing the grooves out. I would be on the floor, between the speakers, listening to every track and that album would (or would not) become the foundation for the rest of my life. Will we see another Floyd or Zep, Wings or Bowie, will the young people get past their three minute attention span to support anything. Because as you say, at the end of the day, it is we, the listeners, who influence the direction of music, but when music is reduced to a digital skip, an albumless album, no more posters, stickers or pride of ownership, what will it mean in twenty years time?

Dave: While I understand the feeling of ownership that comes with buying a record or CD, I don’t really feel like I’ve lost anything by having an entirely digital music collection. Perhaps the physical item was really a greater connection to the artists themselves, and nowadays we can find other ways to make that connection with artists whose music we love.

Perhaps the bigger issue is that digital music is “good enough” for most people. Likewise, the databases that estimate your musical tastes have been “good enough” for most, which is why Pandora, Spotify & Rdio seem to dominate the landscape right now, and those services seem to benefit the major labels the most. That’s my main concern here. The good indie music will fall through the cracks more often than not on services like that. I feel like we still need something that will sift out the RIAA music and point people to the best indie stuff, and I think this still requires a human touch. (The Sixty One has a decent concept for this in place, but they alienated a lot of users a couple years ago, and I’m not sure how far they reach now.)

Well written ,thanks to shows like yours I have discovered ,music and artist,performers

that listening to radio I never would. Thanks to the internet, that I can listen to music

from other lands ,and discovered those on the other side of the world. Currently I wait for your monthly , and every afternoon ,I listen to lounge out of Germany ,France and Spain. I buy the music that I like and have found thru this medium. I miss Dick Clark ,because he guided me and encourage me to listen to others . I grew up listening to salsa ,but once I found Dick Clark and all the artist he brought to the fore front,things changed for me, In todays market there is no-one doing what he did ,and if it was not for guys like you ,music will be stale,since they want you to buy the same old crap(radio stations).Once again ,thanks for being you and for bringing real music to us.